by Author Todd Balf

Todd Balf is a New York Times bestselling writer known for his ability to identify little-known people and events in the worlds of adventure and sports and bring their stories vividly to life. He is author of the critically acclaimed adventure sagas The Last River and The Darkest Jungle and the biography Major, about the pioneering Black bicycle racer Marshall “Major” Taylor. Balfʼs writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Harperʼs, GQ, Outside, Runnerʼs World, and elsewhere. He is also the author of the Everand Original Complications, a memoir about how illness reshaped his own life as an athlete.

1924 Paris Olympics

WHEN THE U.S. OLYMPIC TEAM landed in France on June 25, 1924, they were in good spirits and relatively healthy. The exception was the coxswain of the four-man rowing crew, John Kennedy, who in an unexpected roll of the boat was grazed in the neck by a wayward round fired during modern pentathlon target practice. His readiness for Olympic competition was questionable. Another pentathlete, Sidney Hinds, would shoot himself in the foot when a Belgian marksman absently knocked into him. Despite the wound Hinds scored a perfect fifty in the 400- meter event.

In the excitement of the U.S. team’s arrival at Gare Saint-Lazare station, the world record holder in the breaststroke, John Faricy, broke an ankle in an overeager leap to the platform from the still moving train. His teammate, the brash phenom Johnny Weissmuller, jumped off as well, to grab a baguette from an attractive girl selling them, but struck the landing without incident.

For the rest of his life, Faricy, whose injury kept him out of the Games, would say the sight of French bread made him ill.

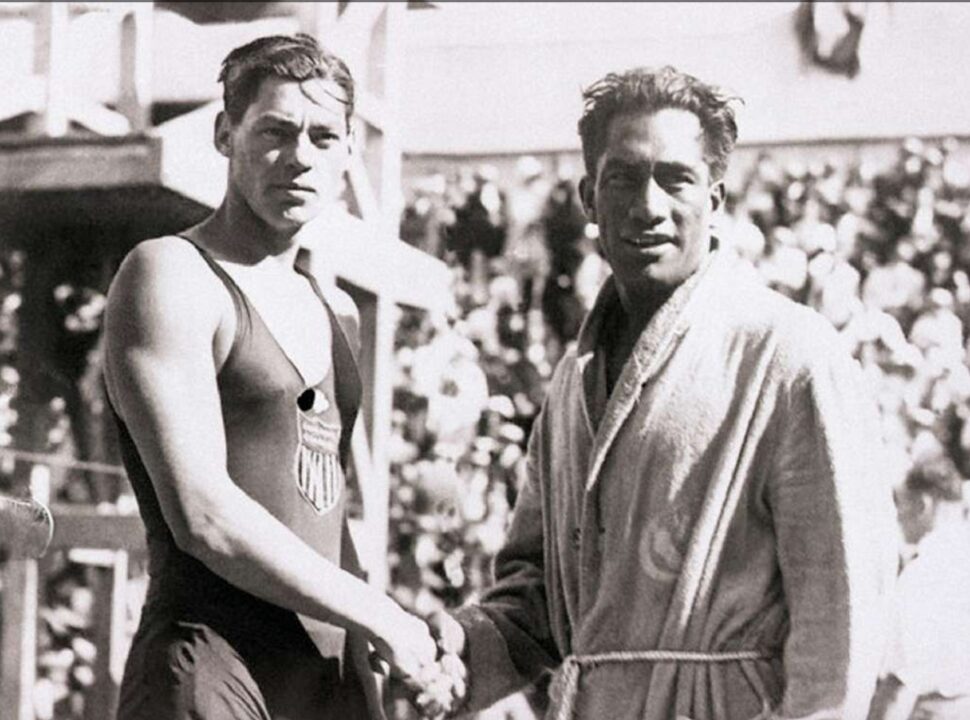

The Paris newspapers were there to record the American invasion, most of the ink devoted to Weissmuller and Hawaii’s Duke Kahanamoku, the two-time Olympic gold medal winner in the 100-meter freestyle. These Games would bring a much-awaited showdown between the twenty-year-old upstart and the thirty-four-year-old elder statesman.

Though the two men were public comrades on the same American team, the Games were still in their infancy, with athletes more aligned with hometown sporting clubs than the stars-and-stripes-branded national organization. Weissmuller was the face of Chicago’s cockily dominant Illinois Athletic Club. Kahanamoku was the face of territorial Hawaii, which had raised the funds for all three of his Olympic appearances. He and his Waikiki beach friends had become locally famous years earlier, when they started their own grassroots club, an answer to the restrictive, white-only clubs in Honolulu.

Hawaiian-bred champions like Duke were seen as the natural product of a semi-civilized ocean environment. By contrast, Weissmuller was thought of as a modern human engineering marvel, the product of the best coaches, the best pool, and the most advanced techniques. Here in Paris, at the first Olympics of the modern age, complete with live radio coverage and celebrity attendees ranging from the Prince of Wales to American film star Mary Pickford to Ethiopia’s Crown Prince, Haile Selassie, they were finally squaring off in competition. It was the most anticipated race in swimming history.

As their qualifying events approached, the buzz intensified over who would prevail. Weissmuller was seemingly unbeatable, having recently shattered numerous world records in pools across the U.S. But Kahanamoku had experience and unmatched power on his side.

Magazines and newspapers were obsessed with the swimmers’ physical numbers — height, reach, and chest size. Weissmuller had smaller feet: size ten and a half to Kahanamoku’s thirteen. The defending Olympic champ had larger hands, too. At nine-and-a-half inches long, they were bigger than a much taller man’s. Future high-flying dunkers like Wilt Chamberlain and Dr. J had similar sized hands but were seven-foot-one and six-seven, respectively.

Kahanamoku was barely six-two. The fascination with Duke’s hands was such that an avid memorabilia collector considered a hastily drawn outline of them on lined notebook paper his most cherished Kahanamoku artifact.

Both Weissmuller and Kahanamoku shared the perfect body proportions of long upper torsos and comparatively short legs, which made for less water resistance. Their wingspan, commonly the same length as a person’s height, exceeded the average. Longer arms equated to longer distance per stroke. People were still not clear on what truly governed speed — early crawl adoptees mistakenly emphasized a fast, windmilling stroke — but it eventually would be apparent that stroke length, along with stroke frequency, produced momentum.

How fast the two swimmers could push each other was the question. It hit upon a larger question that pervaded all human exploits, from running to flying to auto racing to mountain climbing: What was the limit of possibility? At that very moment, British alpinists George Mallory and Andrew Irvine were clawing their way up Mount Everest, the world’s tallest peak, despite the prevailing belief that no one could survive the upper reaches where life-sustaining oxygen was scarce.

Anything was possible in the record-setting age, and pools were where some of it happened. Twenty years earlier, before the freestyle stroke was universally adopted, the barrier to be broken was 100 yards in one minute. Weissmuller was threatening to break fifty seconds, slicing through water at a rate of speed akin to runners circling a park. Running and swimming were interchangeable. Humans had been land animals but they were something else now.

The wild card in the coming showdown was Weissmuller himself. Could the exuberant star stay out of trouble? On the team’s first day in Paris, shortly after stepping off the train, Weissmuller had heard an anti-American jeer from a passing bicycle rider. He chased after the man, dragging him to the ground and badly beating him. He was called before U.S. Olympic Committee officials the next day, and only because of coach Bill Bachrach’s persuasive defense did he avoid being sent home. General Douglas MacArthur, overseeing military members of the U.S. team, wasn’t pleased. Just before they had disembarked the SS America, he had sternly reminded everybody aboard: “Now remember you are ambassadors of the United States, and we expect you to behave accordingly.”

Idle time was nobody’s ally. The Olympic Village, “an army cantonment without any soldiers,” in one writer’s words, looked like a dusty Old West outpost — a smattering of shacks, roads without sidewalks, dirt yards. Every day the swim team left the Piscine des Tourelles outdoor stadium for lunch at Gruber’s American Café, where they returned for dinner following the afternoon training session. Rarely was the team happy with the food or the service, and in the kitchen, the waitstaff grumbled, too.

To pass the time, the Americans bet on wrestling matches. The favorite pairing was the champion swimmer Gertrude Ederle (soon to become famous for being the first woman to swim the English Channel) and the runner Joseph “Joie” Ray, who drove a cab for a living. The U.S. officials eventually found out and put a stop to the matches.

There were numerous formal events where the swim team was expected to be polished representatives of their country. They were feted at the Place de la Concorde and did water stunts at the Sporting Club. There were hundreds of ways for Weissmuller to make the wrong kind of news. The coaches and American dignitaries simply held their breath.

IN THE EARLY ROUNDS OF SWIMMING, news wasn’t made by the Americans, Swedes, or Australians, all of whom advanced as expected, but by the Japanese and British. Both turned heads but for opposite reasons. The British, the original record setters of modern times, had faded faster than anyone thought likely. The Japanese had reversed their fortunes, having dramatically changed everything in a comparative heartbeat — the antiquated strokes and breathing techniques of their last Olympic outing, their unshakable belief in a swimming style that dated back to the samurai era. As they watched the Japanese during training sessions, British experts admitted they were impressed and predicted they would have to look out for them at the next Olympic Games in four years’ time. Instead the early results suggested something unthinkable: They had to look out right now.

They had to beware of one swimmer in particular. In the opening round of qualifiers in the first middle distance event, the grueling 1,500-meter, an unknown nineteen-year-old named Katsuo Takaishi had not only advanced but swam faster than the favored British. At the time, there were few racing coaches in Japan and only two swimming pools, one of which Takaishi and his teenaged teammates had dug for themselves. He was part of a tiny Japanese delegation of twenty-four athletes versus 350 Americans. As an Asian who was dismissed as just one more of the “little yellow men” by the French founder of the modern Games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, Takaishi surely shared a sensibility with the Pacific Islander, Kahanamoku. He knew what it was like to be demeaned as less than.

But he also had the arrogance of Weissmuller. He was a handsome icon with a bright, camera-friendly smile. He would go on to become the first Asian to medal in the Olympics in swimming, and from 1924 to 1928 was considered the leading challenger to Weissmuller’s sprint crown.

Observers in Paris watched Takaishi and saw something unorthodox. One Australian reporter argued that his flutter kick couldn’t account for his speed, given he had small feet and hands “of which any woman would feel proud.” He was clearly double-jointed, which was an advantage. The Australian newspapers would mix admiration with racist stereotypes when Takaishi visited the Commonwealth two years later. The White Australia policy had long barred immigration of Asians and Pacific Islanders. Swimmer Noel Ryan wrote in a coaching bulletin, “[the] Japanese crawl was aided by natural looseness and development of the thighs and ankles — probably made so strong and supple by centuries of squatting around the communal rice bowl.”

Takaishi’s form was marvelous, his agility and flexibility evoking muscle and sinew rather than stiff skeletal framing. He didn’t require freakish hands the size of dinner plates and feet like fins. Takaishi, like many Japanese swimmers to follow, excelled in leg strength, footwork, intuitive feel through the water, and mental fortitude. The fans threw their support behind the small outlier they couldn’t explain but couldn’t help but root for.

AT 2:00 P.M. ON SUNDAY, JULY 20, the sold-out crowd of 12,000 spectators were in their seats in the swelteringly hot Piscine des Tourelles, waiting on the dark-suited French race official to raise his gun for the start of the 100-meter men’s freestyle final. The lineup of swimmers curled their toes at the edge of the pool and assumed a slight crouch. Photographers piled on top of each other in a front-row box beneath the diving platform, and motion picture operators worked the deck. Radio Paris’s Edmond Dehorter, nicknamed “Le Parleur Inconnu” (the unknown speaker), was safely set up. He had been banned at the start of the Games when print reporters protested his “unfair advantage” in broadcasting live, but Dehorter would not be denied, squeezing his ample body into a hot-air-balloon basket to produce windy, bird’s-eye view commentary of the track-and-cycling events at Colombes. Now free to do as he pleased, the bow-tied Dehorter sat behind a plate-sized microphone mounted on a sturdy tripod. Four large loudspeakers lined the upper stadium wall. The French had reserved the 100-meter race for the last two days of competition for the self-evident reason that “in swimming, as in all sports, speed is king.”

The president of the French Olympic Committee, Count Justinien de Clary, his great gray beard spooling to midchest, was in attendance, having already sat through three renditions of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and three American flag raisings since morning. In one of the most U.S.– dominant days in Olympic history, the Americans had won three consecutive races, taking gold in the freestyle relay, the 100-meter women’s backstroke, and the 100-meter women’s freestyle and winning all but one of the other six medals.

“Looks like an American holiday,” said Clary to the American VIPs in attendance. Many of the track-and-field athletes who competed in the weeks earlier had gone home, but some had stayed to see swimming’s battle of the century. The American rugby gold medalist, Norman Cleaveland, had stayed around with the apparently unrealized dream of a midnight journey up a Paris flagpole to swipe an Olympic flag.

If coaches was concerned that Duke Kahanamoku and his brother Sam—another elite Hawaiian on the U.S. team—would race together to defeat Weissmuller, someone had taken care of it by putting Sam in lane one. Johnny and Duke were next to one another in lanes four and five.

There was no evidence that the brothers would have engaged in cynical tactics if the trio were clumped together — for example, Sam and Duke squeezing Johnny by boxing him in and disrupting his stroke. There was no history of such behavior by either brother, but having Sam unavailable to help Duke was a boon to Weissmuller’s positive race psychology. Nervous by nature before a race, Weissmuller could relax knowing the biggest doomsday scenario was erased.

There was a bigger concern, though. Exhaustion. The 400-meter final on Friday had required a Weissmuller effort few had seen before. He had been taken to the limit by Sweden’s Arne Borg and the Aussie Andrew Charlton. He had gathered himself for a triumphant come-from-behind sprint in the final 100 meters, but at an obvious cost. As he posed for photographers, he needed to clutch hold of the guard rope to keep from falling over. In a photo with Charlton, Weissmuller looks spent, arms limply hanging, shoulders slumped, eyes glazed. Inches away lay Borg in an exhausted heap, surrounded by doctors and officials.

Weissmuller was also anxious about how the crowd would receive him. They ran hot and cold, howling at his comedic antics but hissing when he disrespected his competitors. In the 400- meter preliminaries he had drawn the fans’ ire when he waved his hands around on the final lap to, in the words of Paris Times, “show how easily he was taking it.” He had no time to recover, given Saturday’s 100-meter prelims and the 4-by-200 relay final.

In the latter he didn’t have the strongest team to support him. A core group of Chicago-based swimmers replaced the Hawaiians like Duke who had helped win gold for the U.S. in 1920. Still, Weissmuller managed to swim a blistering anchor leg to record a new world-record time.

The Americans knew a good start couldn’t win the 100-meter race but a bad start could lose it. Duke tended to project more steeply downward, eager to get into the water and begin stroking.

Johnny liked to lay out, stretching his long body for as long as it could fly. Moments before he hit the water he didn’t appear to be diving at all; he held his line as straight as a pencil, then dropped his head and angled down, smacking the water with hands, arms, torso, and legs in what he and Bachrach described as a “shallow plunge.” The pancake landing prevented his body from going as deep as most other swimmers at the start. His slightly bent right leg was poised to kick at the same instant he landed.

He was a notoriously slow starter. Bill Bachrach thought he had slow reflexes, and a fast, gun-beating start was all about reflexes. He didn’t want Johnny to try to beat any gun, he said, he didn’t have to. Once in the water, his speed would prevail.

When he started his stroke, he arched his back, kicking his feet six times for every full stroke.

The widest range of Weissmuller’s up and down leg action was no more than eighteen inches. The legs were for maintaining his position; the arms made him go. His head sometimes appeared to be completely out of the water, cocked upward like he needed to see where he was going. He exhaled through pursed lips, then turned his head to the side to inhale, his lungs expanding to take in almost twice the average person’s maximum capacity — almost three gallons of oxygen. He gulped air from the left, and since Duke was in the lane to his left, Weissmuller could check on his form.

When he looked to his left at twenty meters, Duke looked good. They were even. He could see the plume of water that Duke’s rapid strokes and kicks produced; it was a kind of exhaust trail, and it was longer than Johnny’s, or anyone’s. Duke had an immense engine. The rest of the field was more than a yard back. The danger to Weissmuller was falling a yard or two behind and being jostled by the backsplash.

At twenty-five meters they were on world-record pace. The crowd rose on tiptoes, eyes glued to the water line, easily identifying who was who even in the absence of colored caps or club uniforms. One swimmer was white, one wasn’t.

Weissmuller tried not to do anything impulsive, which was against his nature, but in the defined arena of a fifty-meter pool, he was surprisingly adept and disciplined. In Friday’s 400-meter race he performed magnificently. He had matched Charlton’s ferocious pace, then outkicked him to touch first. The margin of the error at the 100-meter was even smaller. An iffy start could be overcome. But at the wall ahead — the race’s first and only turn — he had to be perfect.

The inexhaustible Takaishi, after starting well, was fading, feeling the cumulative effects of racing more disciplines that weekend than any of other finalists. Duke was starting to worry, too, despite his good start and the strong opening twenty-five meters. His body didn’t feel old, but it didn’t feel quite right, either. Sometimes that was okay. After all the races he had done and all the years he had been at it, he knew enough not to get alarmed. One hundred meters was longer than most people realized, and during it, everything could change.

This excerpt appears with permission from BLACK STONE Publishing.

Great writing – especially from a non swimmer. He really set the scene.

A great read !

I knew a bit about Johnny Weissmuller, but clearly knew nothing of his rivals and teammates and really enjoyed discovering the “other” Paris ’24

Weissmuller save people from drowning in one of the Chicago Lakes in the 1920’s and Duke Kahanamoku save people from drowning in the 1930’s in Newport Beach. I don’t know why Duke Kahanamoku was in Newport Beach but its true. Weissmuller also star in aqua shows with Easter Williams in the 1940’s. Weissmuller moved to Mexico and died in Mexico maybe the end of the 1970’s. I don’t remember it exactly when he died.