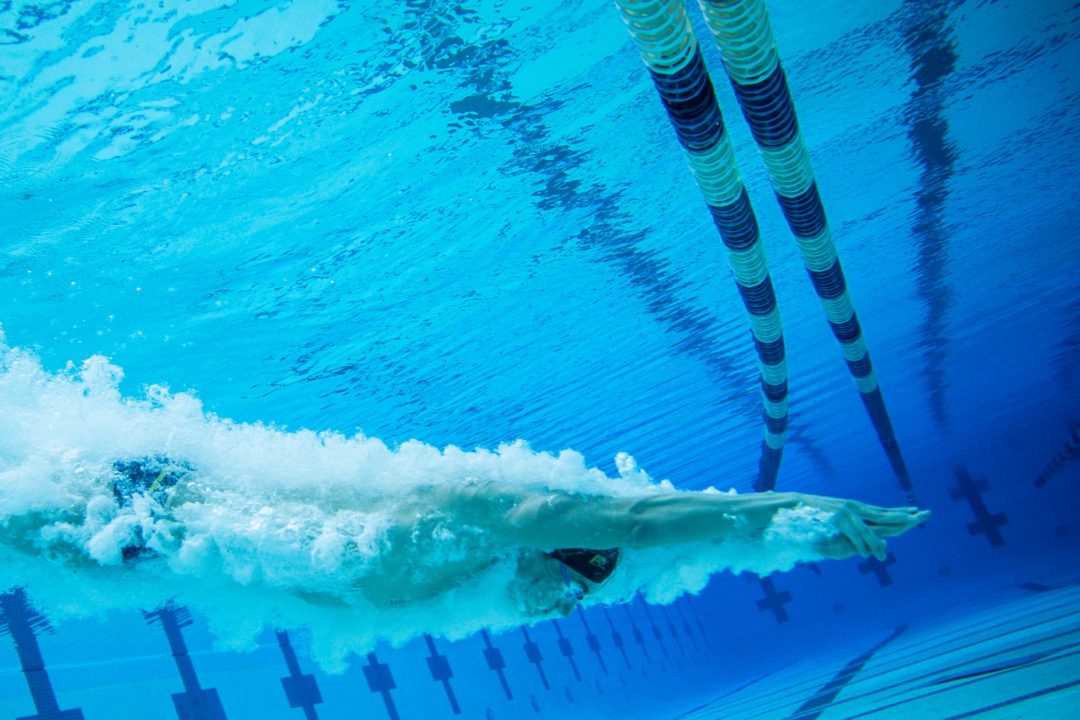

Courtesy: Alexandra Hartman

In recent weeks we’ve seen quite a few of the world’s greatest athletes retire. Serena Williams played her last match at the U.S. Open after 25 years in tennis. Sue Bird just retired from the WNBA, also after a two-decade-long career. David Boudia, a four-time Olympic medalist over three Olympics retired from diving, and will now be pursuing Paris 2024, but in a coaching capacity. Tom Brady’s “retirement” has been all over the news, and it remains to be seen if he’ll ever really leave football.

I have to admit, I felt some relief when Serena Williams announced she would be retiring after the U.S. Open. She’s 40 years old, has been playing the game for over two decades, and made an impressive comeback after suffering some pretty severe health complications while giving birth to her daughter. I even said to one of my coworkers, “Thank God she’s finally retiring; she could have been done a while ago.” Almost immediately I realized how unfair it was for me of all people to say that. I understand better than the average person how hard it is to walk away from athletics.

As a former Division I swimmer, I was nowhere near the caliber of athlete as a Serena Williams, Sue Bird, David Boudia, or Tom Brady. The jump between a DI athlete and an athlete who has been a pro for 2+ decades is pretty tremendous. But at my peak, I got a taste of what those athletes go through. And it’s not nearly as glamorous a life as we are brought up as youngsters to believe. The media shows the highs and very few of the lows and sacrifices required to perform such feats of athletic performance. It’s not the same for everyone, but often you sacrifice a social life, vacations, educational opportunities, and so many other experiences that the average person will likely have.

Of course, you get to travel for competitions and that is a great privilege — but it is far from a vacation. When I traveled for meets in high school and college, all I did was eat, sleep and swim. I would be at the pool from 7 AM until 12 PM for prelims and then have 2-3 hours of time to eat lunch and maybe take nap in my hotel room if I could ramp down enough in between sessions. In the late afternoon, it was back to the pool for finals which could last another 3-5 hours. Then back to the hotel for a late dinner, bed, and then wake up again to do it for another 3-4 days. That sort of travel on top of training 20 hours a week, you were lucky if you had enough energy to do much else when you actually had some free time. You get other perks like free gear, equipment, and other team or sponsored “swag” — again, another privilege I would never dream to complain about; almost two years on, and still most of my wardrobe is college swimming gear.

I can only speak from a swimmer’s perspective — I don’t know to what extent other sports may be more or less time-consuming or strenuous, but in order to achieve athletic excellence it almost always takes an extraordinary amount of time and effort. And like I mentioned above, if you perform, you are rewarded for that effort: scholarships, free “swag”, prize money, special status— you name it. Slowly but surely, everything you have and potentially all of your worth as a person is contingent on how you perform as an athlete. It is your job, and it becomes your life.

And the trouble is, at a certain level, you don’t even realize how much of your day-to-day life it absorbs. It took me about six months of slowly weening myself off of the sport to feel like I didn’t need to swim at least three times a week. Before I retired I had nine training sessions a week. I’ve never gone through a drug or substance withdrawal, but that is the only feeling I can imagine getting “off” of swimming could be similar to. It felt like my body and mind were addicted to the high of being exhausted after practice, the feeling of strength and power going through the water, the sense of accomplishment that came with a best time, a race won, a seemingly impossible practice conquered. No other activity has quite been able to match that feeling. I swam in some sort of competitive capacity for 17 of my 23 years so far on this planet — I can only imagine the withdrawals that a true junkie with double my years’ experience and far greater accolades would feel.

The physical and habitual aspects of retirement are only the beginning. As an athlete, you can read all the self-help articles on how to find life after athletics, and speak to as many retired teammates as you can about how they had dealt with the changes, but no amount of advice can prepare you for what is to come.

The fall after my retirement from college swimming, I began working a corporate job in a brand new city where I knew almost no one. I was sitting for most of the day, had few hours to myself, and no one who could really sympathize with the massive changes I was experiencing. My whole life, being an athlete had given me a purpose and a place. In the moment I had not realized that I really had identified as a “swimmer”. I identified with being lean and athletic, with exceptional endurance and I gained respect through my athletic abilities and my grades. My sole purpose had become performance in the pool and performance in the classroom. Suddenly, no one really gave a damn. Sure, people have respect for what they thought I had done in college, but no one genuinely cared, or knew the lengths to which I had gone to compete at such a high level.

I spiraled into a depression I didn’t believe myself capable of; I developed disordered eating habits when I noticed my body shifting from lean and muscular, to a slightly softer, more feminine form. I would wake up to go to work and have debilitating anxiety attacks that made me feel like my brain and body weren’t my own. Soon enough I was losing clumps of hair, I was a nervous wreck and I told my parents one night over the phone that I felt that there was something inherently wrong with me — that I no longer felt like myself. I would cry most mornings before work, and most evenings when I got home. I am sure my coworkers and managers were concerned about me — I can only imagine what I must have appeared like from the outside. But no one could tell me that I was suffering from a complete loss of purpose — how could they know?

I am doing significantly better now that I have developed a new routine. I wake up almost every morning at 5 AM to go work out before I head into the office. I’ve figured out this alleviates my anxiety attacks and any depressive feelings I might get throughout the week. It gives me energy during the work day and time in the evenings to myself to explore other activities I enjoy and socialize with new people, both of which have been critical to finding a new purpose for myself. I only swim on the weekends now when I feel like it, or go for ocean dips after work when I am feeling particularly overwhelmed or stressed. The water is still my happy place, but I do not feel dependent on it anymore.

I never would have imagined that the end of a swimming career that had peaked out at a DI college level would have poked so many holes into my sense of self. What retirement must be like for a professional athlete that has made their name, their fortune, their whole entire life upon their sport? I cannot even fathom. Voluntary retirement from elite athletics is an unquestionably difficult and life-altering call to make for yourself. No wonder it sometimes takes an injury or some other incident to force an athlete out of the game instead — it’s a hell of a lot of change to bring on yourself voluntarily.

So to those already retired athletes, and those soon to retire — I commend you for this life-altering decision, whether voluntarily made or involuntarily thrust upon you. Here comes the rest of your life, whether you’re ready or not — time to see what else it has in store for you.

ABOUT ALEXANDRA HARTMAN

ABOUT ALEXANDRA HARTMAN

Alexandra is a former collegiate swimmer for the University of Nevada, Reno, class of 2021. She grew up swimming for Palo Alto Stanford Aquatics in the San Francisco Bay Area, beginning at the age of seven, and now lives and works as a recruiter in San Diego, California, and spends as much time as she can in the ocean. “Go Pack!”

At the end of one’s career it is so important to properly grieve the loss. At the very least there is a very good chance that no one will ever again invest in your growth and development like your coaches and team did. Some how, the stakes and bonds in the real world cannot equate to the 400 free relay that MUST be won to win the meet. That loss of that support leaves a void. I am now 20+ years removed from my competition days, but I still remember very clearly how I felt when the Trials rolled around after I had retired. Devastated. I can tell you this. Swimming taught me all of the big life lessons. The… Read more »

Great piece, almost everything about this resonates with my experience.

As a fellow mid major D1 swimmer, I think it is especially hard in some ways because you put in the same time and effort that the best college swimmers do, but because there was never a real chance of a professional career or national team, you don’t feel entitled to your own feelings of loss and maybe struggle to acknowledge how central to your identity the sport had become.

Thank you for writing and sharing!

A nice read. I was the stereotypical average collegiate swimmer x 4 full years, and in my 16 years at full intensity in the sport I wanted so badly to be the elite level, loved traveling for meets, etc. Never got there and lived vicariously through the teammates who did hit national rankings, etc. So even the mediocre milestones hidden in the lesser places of the A/B-Finals at my big taper championship meets were fulfilling enough for me. Having 4 taper meets in one championship season seemed like it was “good enough” for me when I was wrapping up high school.

The effect of hanging up the goggles didn’t really kick in for me until about 18 months after college… Read more »

Great insight and a great read I appreciated this article a lot.

Thank you so much for sharing. I really resonated with this – depression, anxiety, disordered eating, the feeling after swimming, etc. I think something else that’s also incredibly challenging is that tangible goal setting and the high that comes with meeting that goal is so much less. In swimming it’s black and white: go a certain time, qualify for this meet. Do the work to get there.

It’s so much more vague and ambiguous in corporate America. Sure, we can have goals of getting promoted and making more money, but there’s so much more ambiguity in getting there and having to lean on other people’s recognition in order to get there.